BAUHAUS.INSIGHTS: Artistic Interventions Create Points of Contact With the Life and Suffering of Forced Labourers During the Nazi Era

In early May, the Museum of Forced Labour under National Socialism was inaugurated at the former Gauforum in Weimar. The permanent exhibition showcases unique and largely unknown materials from the history of forced labour, providing visitors with the opportunity to deeply immerse themselves in this aspect of Germany’s past through eyewitness accounts and interactive features. The documents, images, and case histories on display have been gathered over many years of research in archives across Europe, the United States and Israel. They tell the story of forced labour, focusing on the relationship between the German majority society and the forced labourers.

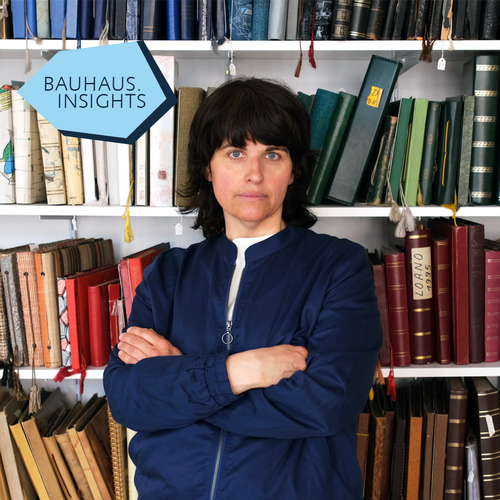

The museum management has partnered with Weimar artist and Bauhaus-Universität Weimar alumna Anke Heelemann to create artistic interventions that highlight the history of Nazi forced labour in the public sphere. People who were turned into forced labourers by the Germans are given a presence in the midst of our everyday lives. In this way, the interventions create unmediated, direct encounters with the past, with the goal of provoking surprise and perhaps discomfort, arousing curiosity and fostering a deeper understanding of history. For BAUHAUS.JOURNAL ONLINE, we interviewed graduate Anke Heelemannto as part of our BAUHAUS.INSIGHTS series to ask a few questions about her interventions.Ms. Heelemann, the art campaign creatively presents historical documents about Nazi forced labour to both online and offline audiences, making an immediate and direct impact on people. How can we envision these interventions taking place in the urban space?

The interventions work with different formats on different levels within the public space. Unexpected encounters with the past can happen in everyday places such as train stations, bus stops, hair salons, gyms, theatres, cinemas, city benches and even in the city’s official gazette. The aim is to create a lasting awareness of the issue, just like forced labour took place everywhere. The project is more or less an extension of the museum, which opened at the beginning of May. Private photographs of forced labourers and the rules and prohibitions that governed them were prepared for different forms of media, such as postcards, SwingCards, posters, envelopes, and more.

All formats are used as »eye-catchers«. A notice prohibiting forced labourers from going out is prominently displayed next to the theatre’s schedule, while a seemingly innocent image of a forced labourer is featured in the middle of the public utility company’s customer magazine. The back page of the magazine offers a memoir and explanation to provide context. In this way, people who were turned into forced labourers by the Germans are given a presence in the midst of our everyday lives.

At the same time, the project confronts the racist rules of the Nazis. The clear object is to deliberately foster a sense of unease. At the same time, however, all media are linked to the museum’s website through QR codes, where comprehensive background information can be found, including the biographies of forced labourers. The project is based on the fundamental idea that it is supported by the city of Weimar. For example, bus drivers display our SwingCards on their buses, or shopkeepers clear out individual compartments in their postcard stands featuring classic Weimar motifs and put our postcards in their place.

How did this collaboration with the museum originate, and how do you perceive your artistic role in this context?

In the course of the museum opening in Weimar, the museum team made it a priority to incorporate the topic of forced labour under National Socialism into the urban space. The collaboration with the Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora Memorial has existed since the exhibition, originally conceived as a travelling exhibition, debuted at the Jewish Museum in Berlin before embarking on a tour across Europe. In 2010, while in Berlin, I created and implemented interventions for public spaces during the opening event. These interventions have since been expanded for use in Weimar and beyond. It’s great that an institution is willing to invest its time and financial resources in exploring new communication opportunities that such an artistic concept offers – moving away from mere marketing and focusing instead on meaningful content and its transfer into the present and people’s everyday lives, precisely where forced labour took place and where responsibility for it lies: in the public eye, in the heart of society. And ultimately, it is about setting an example and honouring our historical and social obligations.

Where do the many photographs of forced labourers come from, and how were the stories of the individuals depicted in the images researched?

The interventions were developed from the contents of the permanent exhibition at the Museum of Forced Labour, which I highly recommend to all. Since 2007, a team of historians has been researching in various archives to develop an exhibition. They have collected many documents, including a large number of private photographs, which was not expected at the outset. It in some cases involved the institutions that were responsible for coordinating the processing of compensation claims of former forced labourers. When compensation was decided and implemented in Germany in the 2000s, these documents were often the only way for those affected to prove their Nazi forced labour. At first glance, the photos appear quite ordinary. It is only when reading the notes on the back or when paired with accounts of forced labour that it becomes evident that these are by no means ordinary personal photographs.

You have had a very personal long-term project, the »FOTOTHEK«, since 2006. Is there a story behind each of the photos?

Certainly, but not just one story. The principle of the FOTOTHEK revolves around constantly revisiting, reexamining, and reflecting on my archive of personal photographs. However, the photographs here are anonymous, and their provenance is not clear. This means that the context of the images is and must be constantly recreated – the stories must be retold. This usually happens in interactive and performative formats in which I use media such as installation, photography, theatre, language and communication. In addition to the anonymous image material, participation and engagement are key components of my analysis. The constant recontextualisation of the material creates its own reflection on the construction of identity in photographs as well as on individual and collective memory.

When you consider today’s deluge of images, will it be possible to effectively convey stories through snapshots in the future, or have they become too contrived to be considered authentic, as well too random? Today there is an abundance of photos that we all carry with us and share on different social networks. Nevertheless, I am certain that, with a certain historical distance, this material can also serve as a source and inspiration – even if the sheer volume of photos and their materiality are difficult to grasp, meaning that the individual image will lose its significance in the larger stream of images. All the material in my archive is still in analogue format, and the FOTOTHEK project also sees itself as an alternative to today’s flood of images. I also believe that the photos today are no less or more contrived than in the past. Of course, more images are edited than before and cover a wider range of topics, but in view of the vast number of photographs and topics, these images provide ample inspiration for artistic exploration. Perhaps they need their story more than ever to stand out in the sea of images. They are also a reflection of our time and naturally of our own selves. Further information: www.museum-zwangsarbeit.de/museum/interventionen_2024 www.vergessene-fotos.de The BAUHAUS.INSIGHTS questions about the »Interventions« were posed by Silvia Riedel and Claudia Weinreich.