BAUHAUS.INSIGHTS: How the »Democrazy?« Project Module is Seeking to Boost Voter Turnout in Thuringia

The state election on 1 September marks the end of the 2024 super election year in Thuringia. But how can citizens be encouraged to vote – and thus to participate in democratic co-determination? A number of institutions and initiatives have given this question some more thought this year, including two professorships from the Visual Communication programme within the Faculty of Art and Design at the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar.

In the summer semester, teaching staff from the Image–Text–Concept and Cross-Media Moving Image departments invited students to develop campaign formats and films as part of the »Democrazy?« project module – with the very specific aim of striving to increase the voter turnout in Thuringia. They teamed up with the Thuringian »Landeszentrale für politische Bildung« to encourage people to vote. The outcomes were displayed in Weimar’s Atrium shopping centre for three days as part of the summaery.

We wanted to know about the different approaches the students took, what challenges the political context presented – and naturally also which of the campaigns the »Landeszentrale für politische Bildung« chose. Hence we spoke with Masihne Rasuli as part of our BAUHAUS.INSIGHTS series for the BAUHAUS.JOURNAL ONLINE. The artistic associate from the Department for Image–Text–Concept led the module together with Prof Burkhart von Scheven, Prof Jakob Hüfner and Nele Seifert from the Department for Cross-Media Moving Image.

Ms. Rasuli, what motivated the four of you to develop this project module?

Democracy is currently facing major challenges in Germany. According to a study by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, while trust in democracy is stable overall, cracks are beginning to develop: Crises such as the coronavirus pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine are fuelling movements that openly question democracy as a form of government. The global political situation has become so complex that people sometimes yearn for simple and quick solutions. Some are no longer willing to accept that democracy works more slowly and democratic participation requires compromises. This dissatisfaction is among others expressed through the conscious decision not to vote in elections; 35 percent of people took this approach in the 2019 state elections, for example. The democratic culture of debate has also changed: Opinions are increasingly rejected vociferously or ignored entirely instead of being discussed objectively. The internet gives people the opportunity to generalise, denigrate and incite hatred anonymously. Enraged citizens gather outside the homes of politicians and campaigners are violently assaulted.

These attacks on democracy and the 2024 super election year in Thuringia inevitably brought the topic to my – and our – attention. We had already ascertained during prior discussions that both departments wanted to address the topic of democracy this summer semester – so pooling our resources to offer a joint project was a no-brainer. As a university, we’re an impartial institution, hence we did not focus on the parties’ political agendas, but rather on the state of democracy in general and on the voter turnout in particular. Through our cooperation with the »Landeszentrale für politische Bildung«, we had a partner with the specific wish to show films and campaigns developed by us in the run-up to the state elections to help boost the voter turnout.

Before beginning the practical component, you first explored democratic processes and raised the question of why the number of people voting in elections continues to decrease while the number of those wanting more of a say is at the same time increasing. How did your findings influence the students’ work?

We began the project with a field trip to the Haus der Weimarer Republik to learn about how Germany’s first democratic constitution was drafted in Weimar in 1919. One fascinating insight was how immensely elaborate measures were taken during the elections for the National Assembly to enable all eligible voters to exercise their right to vote – ballot boxes were even brought to the homes of war invalids, for example. In 1919, the voter turnout was 83 percent in the end.

We had the national spokesperson for the organisation Mehr Demokratie e. V., Ralf-Uwe Beck, as our guest during the plenary session. He gave an impressive presentation on the development of direct democracy in Thuringia. As an activist, he was instrumental in ensuring that direct democracy on the municipal level was accorded a strong position in the Thuringian constitution. Citizens only need 300 signatures to get a topic added to the agenda of a local council, for instance. Mr. Beck gave an impressive account of the rights that democracy grants each and every individual – and that its development is not yet complete and participation can still be improved.

The students then conducted their own field research: Places in Thuringia were selected at random; in this case, simply by throwing a dart at a map of Thuringia. The students travelled to these places in small teams and asked the locals about their attitudes to the upcoming elections. The results of this mini-poll were mixed: All attitudes were represented – from complete disinterest to mistrust and enthusiasm. At the same time, some truly fascinating stories came to light, such as about how some small villages don’t have their own polling stations, so the inhabitants essentially all embark on a trip to a neighbouring village together to vote. We learned from this preliminary work that in order to reach a broad target group, our campaigns definitely could not be limited to social media, but that we would have to develop multimedia formats that would also work in public spaces, as emails and as part of guerilla strategies. The story of the villagers who all go to the polling station together inspired the campaign »Mit wem gehst du zur Wahl?« [»Who will you go vote with?«] and the idea of introducing Thuringian election helpers was born during our tours through Thuringia. The students were so impressed with our guest Ralf-Uwe Beck’s knowledge of democracy and his background as a civil rights activist during the GDR era that they later filmed an interview with him.

What ideas do students use in their campaigns to encourage people to vote?

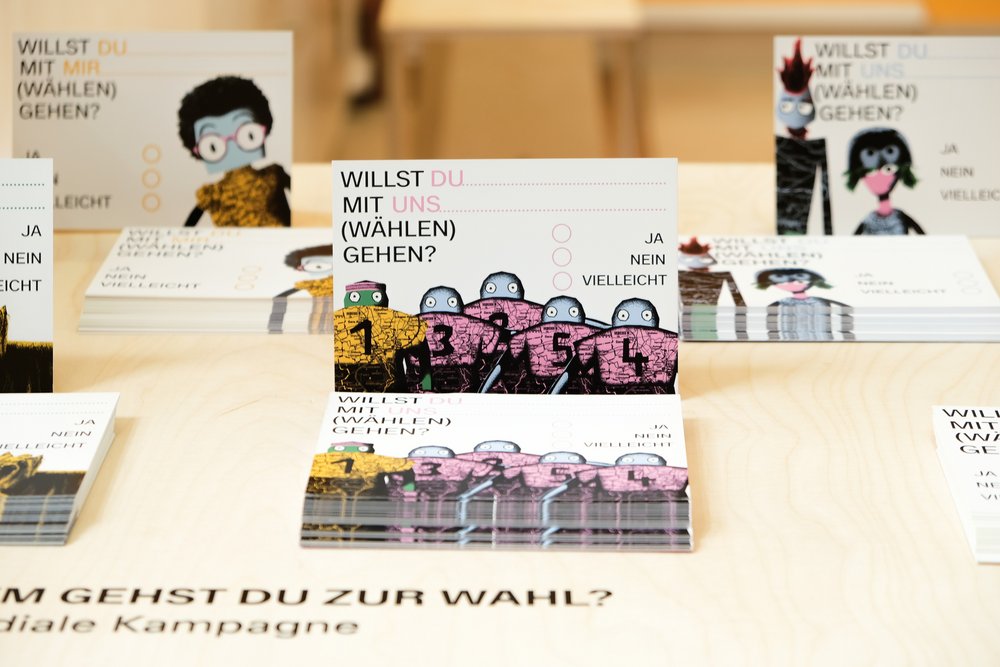

»Who will you go vote with?«

This campaign takes the simple approach of assuming from the outset that people intend to vote in the election. So the question is not whether to vote, but who to go to the polling station with. This question is answered in a series of animations and posters showing unusual pairings on their way to vote, for example a skateboarding granny with her granddaughter. The campaign uses collage illustrations to express this diversity in an abstract and humorous way. People are able to send postcards featuring the campaign motifs to arrange a polling station date with the person of their choosing. The campaign aims to subtly convey that democratic participation is not just a duty, but a privilege – and that it is a social experience that we can have together.

»Mit wem gehst du zur Wahl?«

Click the Play button to load and view external content from Vimeo.com.

Automatically load and view external content from Vimeo.com (You can change this setting at any time via our »Data protection policy«.)

(c) Paula Gerharz, Sebastian Günter, Kevin Kulke, Philipp Merschkötter

»The one choice that really counts«

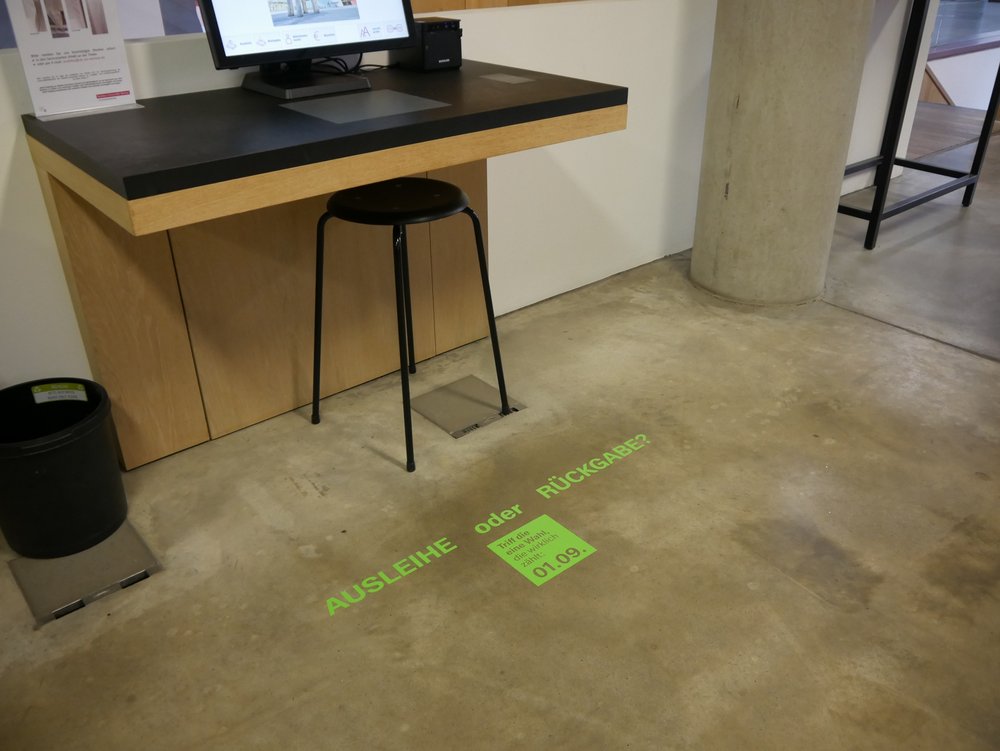

»The one choice that really counts« campaign is based on an interesting finding: Neuroscientists have determined that people make around 20,000 decisions every day. Most of these decisions are relatively mundane, like »Should I use the front door or the back door to get on the bus?«, or »Should I pay using cash or card?«. These decisions do not typically have long-term consequences. Deciding who to vote for, on the other hand, influences the political landscape for years. By pointing out the countless trivial decisions we make every day, the campaign aims to highlight the importance of the decision made at the polls. The campaign includes posters and reels, as well as interventions in public spaces. The interventions are visually staged so that people literally stumble across them. In the university stairwell, for instance, the question »Lift or stairs?« is posed, followed by the answer: »Make the choice that really matters on 1.9.«.

»Die eine Wahl, die wirklich zählt«

Click the Play button to load and view external content from Vimeo.com.

Automatically load and view external content from Vimeo.com (You can change this setting at any time via our »Data protection policy«.)

(c) Leonie Arens, Annika Daub, Lea-Sophie Groß, Antonia Pfadenhauer

»Don’t fear the cross«

The election ad »Don’t fear the cross« works in a hyperbolic sense. Various situations are depicted with people developing a fear of crosses – for instance when looking at grocery lists, road signs and keyboards. These exaggerated images are meant to draw attention the declining voter turnout and to illustrate how unfounded reservations about voting are. Ads and communication campaigns are naturally designed to work as quickly as possible and to convey their message in short narratives. The resulting documentaries complement these campaigns quite well as they can go more in depth in terms of content.

VoteTheFuck - Kreuzphobie

Click the Play button to load and view external content from Vimeo.com.

Automatically load and view external content from Vimeo.com (You can change this setting at any time via our »Data protection policy«.)

(c) Lucian Engelbrecht, Max Tillack, Klaus Merbach, Eric Beck, Nino Schmidt, Luisa Raduenz, Aaron Möbius, Tillmann Böhnke, Alexander Scharf, Rebecca Hilbel, Alaina Nugnis, Philine Vogelsang, Pia Blasius, Moritz Lang, Marcel Sänger, Jonas Turtschan, Dominik Kämmer, Louis Czauderna

»Wahllokal 37 – die Auszählung«

The film »Wahllokal 37 – die Auszählung« accompanies Weimar election workers as they carry out their volunteer work for the European elections. The film gives viewers an inside look at parts of the election day that remain invisible to many, but that are absolutely crucial in the end. It reveals the precision and conscientiousness with which democratic elections are conducted and the commitment of the many volunteers who work to ensure that everything runs smoothly.

(c) Johann Knösel, Philine Vogelsang, Rodrigo Xavier

Birgit Krüger and Ralf-Uwe Beck in film interviews

This film includes moving interviews with Birgit Krüger and Ralf-Uwe Beck, the latter of whom was a guest during our project plenary sessions. The two report on their individual experiences as witnesses of the non-democratic GDR system. Birgit Krüger was imprisoned in 1977 in the GDR because she had applied to leave the country. She spent eleven months in prison, separated from her children, before being ransomed by the FRG. Ralf-Uwe Beck was a pastor in the GDR and an environmental activist. In his interview, he describes his life near the heavily guarded inner-German border, his fight against the injustices of the regime, and the spirit of optimism once it ended with all its hopes and missed opportunities. These discussions show the inhumanity of non-democratic regimes, the valuable achievements of democracy and that democratic participation is still possible today.

(c) Johann Knösel, Philine Vogelsang, Rodrigo Xavier

What challenges did students face?

To convey its message, a communication campaign must be emphatic yet uncomplicated and strike the right tone. The first challenges arise while preparing the texts; quite simply, countless variations must be written and tested. The next step involves combining the message with an eye-catching, memorable design. It’s important to consider different formats here: Do the visual effects work equally well in print, online, in films and in public spaces? One further challenge is of course to develop a design that is as original as possible and stands out from the flood of media images. The students must have a great deal of perseverance, as they must adapt their designs repeatedly and sometimes even start entirely from scratch again.

As some of the topics addressed in the documentary films involved sensitive personal experiences, a great deal of tact was required when conducting the interviews. What’s more, high-quality footage had to be collected within a limited amount of time, with no possibility to redo it. Film shoots generally require a great deal of technical and logistical expertise – skills that the students were able to pool wonderfully through good teamwork and with the support of us teaching staff.

The campaign formats and films were designed for the »Landeszentrale für politische Bildung«. We’re dying to know, of course – can you already reveal which campaigns will be shown? And what impact the collaboration had on the students?

The »Landeszentrale für politische Bildung« would like to share all of the campaigns we created via its social media channels. Individual ads will also be shown in cinemas across Thuringia. The Bauhaus-Universität Weimar will disseminate the campaign »Mit wem gehst du zur Wahl?« [»Who will you go vote with?«] itself. The campaign »Die eine Wahl, die wirklich zählt« [»The one choice that really counts«] will be shown in public spaces in Weimar, including the Brotklappe bakery, in the form of small-scale interventions. We’re also delighted that the »Landeszentrale für politische Bildung« will use the logo we revamped for the campaigns. We realised early on in the design process that their existing logo was outdated and did not adequately communicate their objectives. The students’ first task was therefore to create a new corporate design for them. One design was then selected in a democratic process for use during the summaery. The »Landeszentrale für politische Bildung« liked this logo so much that it decided to also use it during the election campaigns.

It’s not yet clear whether the »Landeszentrale für politische Bildung« wishes to change its logo permanently. But we have expressed our willingness to support the students should this be the case. This would not only grant them a larger platform for their campaigns, but perhaps even allow them to have a lasting impact on the client’s image. This still needs to be clarified however. Overall, we were allowed a great deal of creative freedom during the collaboration. This was a positive experience for the students, of course, especially since they will have far fewer opportunities for this later on in their professional careers.

More information: Over the coming weeks, we’ll also share the students’ work from the »Democrazy?« project module via the university’s official social media channels to encourage people to vote in the state elections on 1 September 2024.

Instagram: @bauhaus_uni | LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/school/bauhausuni

The BAUHAUS.INSIGHTS questions on the »Democrazy?« project module were asked by Marit Haferkamp in collaboration with Luise Ziegler.