mNo edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

==Learning the Grammar of Animacy (inspired by Kimmerer)<ref>Robin Wall Kimmerer, The Democracy of Species</ref>== | ==Learning the Grammar of Animacy (inspired by Kimmerer)<ref>Robin Wall Kimmerer, The Democracy of Species</ref>== | ||

<blockquote>''<nowiki>''</nowiki>I come here to listen, to nestle in the curve of the roots in a soft hollow of pine needles, to lean my bones against the column of white pine, to turn off the voice in my head until I can hear the voices outside it: the 'shhh' of wind in needles, water trickling over rock, nuthatch tapping, chipmunks digging, beechnut falling, mosquito in my ear, and something more - something that is not me, for which we have no language , the wordless being of others in which we have no language, the wordless being of others in which we are never alone.'' | |||

''[...]'' | |||

''Listening in wild places, we are audience to conversations in a language not our own.'' | |||

''[...]'' | |||

''To name and describe you must first see, and science polishes the gift of seeing. I honour the strength of the language that has become a second tongue to me. But beneath the richness of its vocabulary and its descriptive power, something is missing, the same something that swells around you and in you when you listen to the world. Science can be a language of distance which reduces a being to its working parts; its a language of objects.<nowiki>''</nowiki>''</blockquote> | |||

== '''Internal imagery and exploratory sketches'''<ref>R. Murray Schafer, A Sound Education: 100 Exercises in Listening and Sound-making</ref> == | == '''Internal imagery and exploratory sketches'''<ref>R. Murray Schafer, A Sound Education: 100 Exercises in Listening and Sound-making</ref> == | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

I was inspired by Schafer's "A Sound Education: 100 Exercises in Listening and Sound-Making." | I was inspired by Schafer's "A Sound Education: 100 Exercises in Listening and Sound-Making." | ||

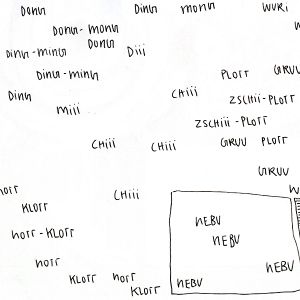

== Exercise 1 == | |||

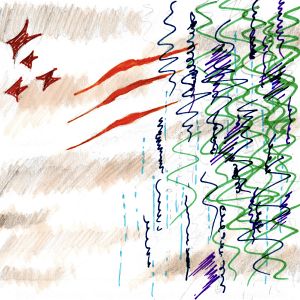

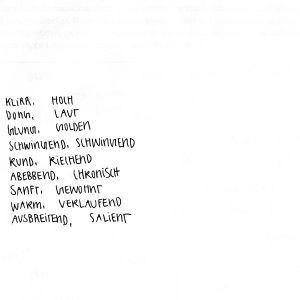

'''The process begins with a focus on internal visualization and exploratory sketches, encouraging you to translate what you hear into a visual format. This method invites a deeper engagement with sound, elevating listening from a passive act to an active, multi-sensory experience.''' | '''The process begins with a focus on internal visualization and exploratory sketches, encouraging you to translate what you hear into a visual format. This method invites a deeper engagement with sound, elevating listening from a passive act to an active, multi-sensory experience.''' | ||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

[[File:Ex1.3.jpg|left|frameless]] | [[File:Ex1.3.jpg|left|frameless]] | ||

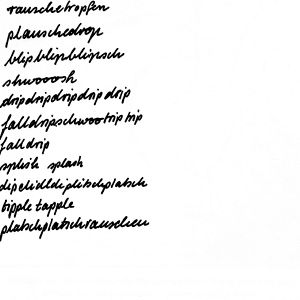

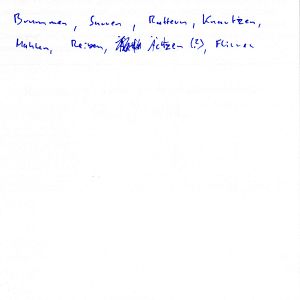

== Exercise 2 == | |||

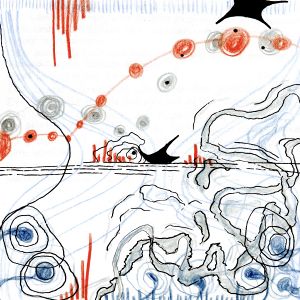

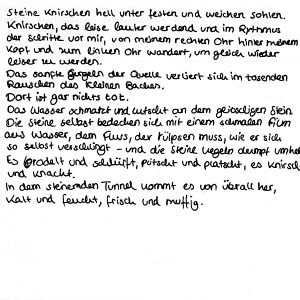

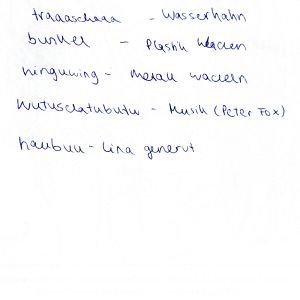

'''The second step involves reconnecting with these auditory experiences through language. By using familiar words and descriptive phrases, you may gain a deeper understanding of the soundscape while framing it within the context of your own linguistic and cultural background. This phase helps to bridge the gap between abstract auditory sensations and the structured world of verbal expression.''' | |||

Language as a reflection of your soundscape: Use several words to describe a sound from your environment (e.g., gurgling, splashing, bubbling, ...).[[File:Ex2.1.jpg|left|frameless|[[File:Ex2.2.jpg|left|thumb]]]] | |||

| Line 51: | Line 54: | ||

[[File:Ex2.3.jpg|left|frameless]] | |||

[[File:Ex2.4.jpg|left|frameless]] | |||

[[File:Ex2.2.jpg|left|frameless]] | |||

| Line 57: | Line 63: | ||

| Line 72: | Line 77: | ||

[[File:Ex2.5.jpg|left|frameless]] | |||

| Line 85: | Line 90: | ||

[[File:Ex2.6.jpg|left|frameless]] | |||

| Line 100: | Line 103: | ||

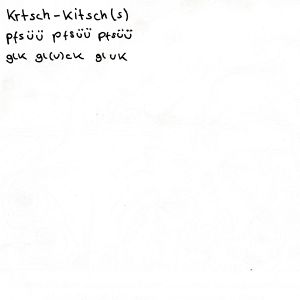

== Exercise 3 == | |||

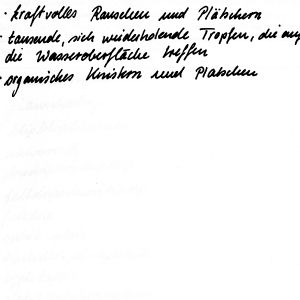

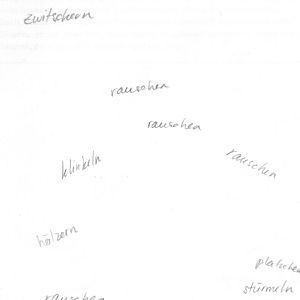

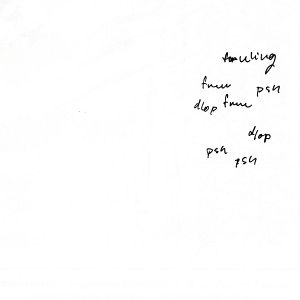

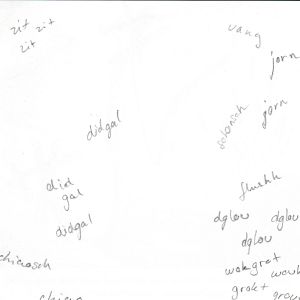

'''In the final phase, we move beyond conventional boundaries, venturing into uncharted territory by creating entirely new words to describe the sounds we perceive. You are encouraged to place these unique terms freely and creatively on the page, breaking away from the constraints of traditional grammar or format. This stage fosters a playful and imaginative relationship with sound, allowing for a more personal and expressive connection to the auditory environment.''' | |||

Find onomatopoeic words for sounds like raindrops, streams, waterfalls, rivers, or ocean waves, for example: ''clasticy-shash, geeshian, retzensplats, gurglewoo, plittertonk, blibliboop, hwoosh, piddlip, splish, spankle-spickle, pli-pli...'' | |||

Invent one unique onomatopoeic word for each sound you hear. | |||

[[File:Ex3.2.jpg|left|frameless]] | |||

| Line 115: | Line 120: | ||

[[File:Ex3.3.jpg|left|frameless]] | |||

[[File:Ex3.4.jpg|left|frameless]] | |||

[[File:Ex3.5.jpg|left|frameless]] | |||

[[File:Ex3.6.jpg|left|frameless]] | |||

[[File:Ex3.7.jpg|left|frameless]] | |||

| Line 127: | Line 137: | ||

| Line 150: | Line 150: | ||

| Line 166: | Line 160: | ||

Revision as of 18:30, 4 January 2025

Learning the Grammar of Animacy (inspired by Kimmerer)[1]

''I come here to listen, to nestle in the curve of the roots in a soft hollow of pine needles, to lean my bones against the column of white pine, to turn off the voice in my head until I can hear the voices outside it: the 'shhh' of wind in needles, water trickling over rock, nuthatch tapping, chipmunks digging, beechnut falling, mosquito in my ear, and something more - something that is not me, for which we have no language , the wordless being of others in which we have no language, the wordless being of others in which we are never alone.

[...]

Listening in wild places, we are audience to conversations in a language not our own.

[...]

To name and describe you must first see, and science polishes the gift of seeing. I honour the strength of the language that has become a second tongue to me. But beneath the richness of its vocabulary and its descriptive power, something is missing, the same something that swells around you and in you when you listen to the world. Science can be a language of distance which reduces a being to its working parts; its a language of objects.''

Internal imagery and exploratory sketches[2]

The worksheets I have created are designed to help heighten awareness of the soundscapes in our immediate surroundings.

They begin with an internal image, combined with exploratory sketches, inviting us to elevate listening to a new, visual level. In the next step, we use language to reconnect with the soundscape in a familiar way. Finally, we move beyond conventional expressions and create our own new terms for the sounds we perceive, which can be freely and creatively arranged on the page.

I was inspired by Schafer's "A Sound Education: 100 Exercises in Listening and Sound-Making."

Exercise 1

The process begins with a focus on internal visualization and exploratory sketches, encouraging you to translate what you hear into a visual format. This method invites a deeper engagement with sound, elevating listening from a passive act to an active, multi-sensory experience.

Find a place where you can fully engage your senses— step outside your room if you’d like. Spend some time listening closely to the movement of sounds in your environment.

Create a visual representation of the soundscape around you. Use colors, shapes, and patterns to express the sounds—avoid using any words.

Exercise 2

The second step involves reconnecting with these auditory experiences through language. By using familiar words and descriptive phrases, you may gain a deeper understanding of the soundscape while framing it within the context of your own linguistic and cultural background. This phase helps to bridge the gap between abstract auditory sensations and the structured world of verbal expression.

Language as a reflection of your soundscape: Use several words to describe a sound from your environment (e.g., gurgling, splashing, bubbling, ...).

Exercise 3

In the final phase, we move beyond conventional boundaries, venturing into uncharted territory by creating entirely new words to describe the sounds we perceive. You are encouraged to place these unique terms freely and creatively on the page, breaking away from the constraints of traditional grammar or format. This stage fosters a playful and imaginative relationship with sound, allowing for a more personal and expressive connection to the auditory environment.

Find onomatopoeic words for sounds like raindrops, streams, waterfalls, rivers, or ocean waves, for example: clasticy-shash, geeshian, retzensplats, gurglewoo, plittertonk, blibliboop, hwoosh, piddlip, splish, spankle-spickle, pli-pli...

Invent one unique onomatopoeic word for each sound you hear.

These exercises are not merely about hearing but about listening with intention, observing with curiosity, and expressing with creativity. The worksheets may provide a structured yet open-ended framework for engaging with the acoustic dimensions of the world around us.

Closing questions may include:

What constitutes sound?

How do sound events emerge from elastic bodies?

How can sound be visualized?

What are the symbolic, aesthetic, and emotional depths of (in this case) flowing water?