No edit summary |

(psyco) |

||

| Line 212: | Line 212: | ||

=Basics of Psychology= | =Basics of Psychology= | ||

Interaction Design is heavily influenced by psychology. No wonder - we are dealing with creating things that are used because of the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Motivation motivations] of the users and are easy to use because it maches the way they [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitive_science think.] | Interaction Design is heavily influenced by psychology. No wonder - we are dealing with creating things that are used because of the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Motivation motivations] of the users and are easy to use because it maches the way they [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitive_science think.] | ||

What you should be aware of is that there are some things that are "expensive" regarding our cognition. One of thiese things is learning new things and getting them into our long-term memory e.g. how you do a certain action in a program. An other is keeping things in short term memory. An example for this would be to remember which function you triggered previously or which item you copied into the clipboard. | |||

==Mental Models== | ==Mental Models== | ||

The way real world things work is represented in our mind as a so-called mental model. The whole world with all its properties can't get in our mind. It would be too much data and what we percieve is heavily filtered anyway by our senses. | The way real world things work is represented in our mind as a so-called mental model. The whole world with all its properties can't get in our mind. It would be too much data and what we percieve is heavily filtered anyway by our senses. | ||

| Line 228: | Line 230: | ||

=Basic Principles& Best Practices= | =Basic Principles& Best Practices= | ||

There are some principles in interaction design that should be followed. It is no crime to break the rules – but you should have a good reason to do so. During the years quite may of them emerged. I collected and explained the ones that I consider as important and easy to apply. | There are some principles in interaction design that should be followed. It is no crime to break the rules – but you should have a good reason to do so. During the years quite may of them emerged. I collected and explained the ones that I consider as important and easy to apply. | ||

==Metaphors== | |||

One way to ease the dealing with a something new is to suggests that it works similary to something the user already knows. This is often done to transfering real world principles to software interfaces and is also known as using a "metaphor". Like metaphors in language the metaphor transfers some aspects while some are not transferred - thats often good: if you do otherwise and try to transfer every single aspect you often end up with a use that has no advantages over the real world thing the metaphr is drawing from but is far more difficult to use. | |||

There are many metaphors around when you take a look at your computer's applications. The most times you will use metaphors by choosing a suitable name or icon for a function or desinging the workflow like a well known process. Though here are two examples of well known metaphers that almost rule the way we deal with the applications they are used in: | |||

* '''The Desktop'''<br> | |||

A classic Metaphor. Like in you real desktop you can put documents you currently deal with, on your desktop and organize your workspace. Many aspects of a real world desktop were not transferred for good reasons. The recycling bin e.g. is usually not seen on top of your real world desktop. But it is pretty useful that it is on your computer's desktop. | |||

[[File:http://web.uni-weimar.de/medien/wiki/File:Tools_GIMP.png|thumb]] | |||

*'''tools'''<br> | |||

You hardly notice this metaphor. Its pretty good. We use tools all the time in our real life and we easyly know how to use the tools on the toolbar in our image editing program: The eraser deletes stuff, the brush paints with color etc. | |||

Metaphors seem to be simply great at the first glance. But they can cause a lot of problems too. They can constrain the user because real world constrains do not apply in the computer. In bad cases the whole interface just follows the metaphor instead of the users needs. This happened in "Microsoft Bob" which was a desktop replacement using a house as metaphor. To access different kinds of applications you needed to go to different rooms. To start the word processor you clicked on a sheet of paper on the desk in the living room etc. The use was cumbersome and unintuitive, so Bob did not succeed. Not as bad as Bob but worth mentioning is the interface of QuickTime 5 that used a wheel to change the sound intensity. So... how do you turn a wheel using your mouse? It turned out that it the usual linear movement worked as well - the same you do when you use a normal slider. | |||

Metaphores can ease interaction - but bad metaphors can cause a lot of trouble. It is often better go see if any standard exists - thats what the following chapter is about. | |||

==Standards and Consistency== | ==Standards and Consistency== | ||

[...] | |||

Like metaphors standards ease learning because you can build on something the user already knows. | |||

==Visibility== | ==Visibility== | ||

==Modeless Design== | ==Modeless Design== | ||

Revision as of 19:48, 22 October 2010

A Students Guide to Interaction Design Solltest ihr irgendwetas ändern: bitte beachtet, dass eure Beiträge unter Creative Commons Lizenz stehen werden. If you change something, please note that this work and you edits are licensed under a Creative Commons

Licence: This work is licenced under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported.

Preface

goals: This guide is aimed at students who want to develop new products, services, software or websites. We cover the whole interaction design process in a brief and understandable way and enable students to understand the most important terms so that they can read the literature.

No-Goals: Include material that is non-relevant for practical work.

Foundations

Iterative Design Process

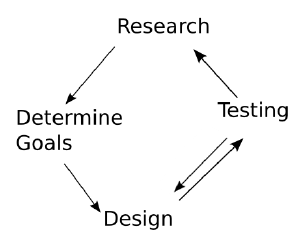

The iterative design process helps you to structure your design process. It is an easy to use cycle model, which steps you can follow. The Process of doing so is explained in this guide.

The steps are:

- Research: in which you gather informations about user goals, existing problems and already existing solutions.

- Formulating you aims: Helps you to know what you actually want to archive with your design (and what not!). This can be seen as belonging to research but it is crucial to make the research useful, so it's got its own bullet-point!

- Design: Is creating solutions for what you want to archive. You start with a broad design of that is fairly abstract and make your ideas more concrete over time.

- Testing: After you designed you need to test if your ideas work as you expected. This is can be a hard thing to do because some things that seem to be great turn out to be unsuitable for your users. Otherwise you will get all sorts of interesting insights that will help you in improving your ideas.

The model is called iterative because you will go through the all or a part of the steps several time. Doing all steps one after the other one time is known as an "iteration". Each time you do so, you improve your product and former abstract things will become more concrete.

The model can be applied for designing the general product as well as for designing a small feature. You don't need to do all steps each time you try to solve a problem. It is very common to design, test and refine the design based on the test's results to test again. But you should at least consider the possibility to research.

So what is all that good for? Following the steps helps you to understand your users by doing research. So you don't design for non-existing needs or interfaces nobody can use. It helps as well to be more creative at the end: by dealing with your users, you will see your designs from a new perspective and so develop new ideas.

A small Example

Imagine you design a new mobile phone. You can use the process that is suggested here to design the general product: You will research how people will use the phone, you will determine which features you need for meeting the users needs. Than you will design how all features work together in the phone and how it will look like. At the end you test it.

During this process you will see that you need to answer smaller questions like how to implement sending messages: Is it better to have different facilities for SMS, MMS and e-mail, or shall they be combined in one view so that the user can ignore the differences between the different techniques?

For getting to know how to deal with this you can again use the cycle model:

1) Find out how the users think about messages and how they use them.

You may find out that users think of their messages all in the same way when they get them but in technical terms when they write them

2) Write down what you need to keep in mind when you design

I want to design a unified view for incoming messages while still providing explicit control over self initiated or reply-messages

3)Than you design...

4)...and test.

Example:It turns out that your design was overall easy to use but that some users had trouble with selecting the message type while sending

What you do now is trying out different ways to make the type-selection easier, so you just repeat the "mini-cycle" of testing and design.

Usability Goals

The usability goals are a collection of the very basic user needs that need to be met. They are broad, but you will have no trouble to understand them.

Utility

If your product's functionality matches the needs of your users and enables them to reach their goals it has a good utility.

You can find out your users needs and goals by doing "user research" which means that you apply some research methods. One of these methods is doing a special kind of interview with some users. I will cover this technique in a latter chapter.

Learnability

A good learnability exists if the users you target can use your product without putting a lot of effort learning. This is especially important for the very basic functions.

Ideally users don't have to bother about new concepts and unknown terms.

Learnability is what will be the first thing that comes into your mind if you think about interaction design. Paradoxically it is a principle that is ignored in many products: Industry often uses a lot of functions that diminish learnability and many student projects ignore learnablity and focus on efficiency. You can improve the learnability of your application by learning common principles of design like "visibility" or "consistency" and by testing your ideas with your users. Material for learning this will be provided in latter chapters.

Efficiency

Your product has a good efficiency if the user can archive a high productivity. This simply means he/she can do more in less time once it is known how one uses the product. Efficiency can be archived with optimizing the ways the functions are accessed and with providing additional ways of interaction like keyboard shortcuts. Efficiency is important, but in my experience it is easiely over-emphasized as one does not need to learn one's own designs and efficient stuff feels just great. But a command line interfaces or gestural interaction are cool and really efficient if you can use it but they need to be explicitly learned before they can be used. And the difficulties of learning are often underestimated by interaction design beginners.

Safety

Safety is protecting the user and his/her creations from undesired outcomes. Very basic is that you provide a product that does not crash and destroys the users data by doing so.

You should as well prevent that the user selects data-destroying functions by accident. E.g. putting the "save" and the "close" entry close to each other in a menu will cause data loss: if the user wants to save, he may press "no" after a dialogue window appears: "don't bother me now. I want to save my data!" - and the data is lost, "close" was selected by accident and the dialog-window that was dismissed by choosing "no" was the final warning.

Even if you prevent accidental actions the users data is not save. Users may misunderstand the name of an action or just try out what the result will look like. Therefore you should provide an undo-facility. This means the user can do an action and if it turns out that this has been a bad idea it can be undone. This is a great feature that demands a bit of thinking when the code is written but it is worth it. As a side effect your application becomes more learnable as well: users are able to learn by doing without any worries.

Simplicity

When I say simplicity I do neither mean "ease of use" nor "looking shiny and smooth". The kind of simplicity I mean in this chapter is implementing only the features that are important for your idea and to implement them in a way that they work together greatly. You should not add anything because it is a nice to have or one in ten people thought it would be useful. Every time you add a feature, you need to make it fit to the rest of your product. It potentially will make it slower, less solid and more difficult to use. And keep in mind: the resources you use to add features (you are probably student so it is: time) can't be used for refining the really crucial features.

So how do you decide which features you are going to implement?

I don't have any instant solution. The most important is that you keep in mind that you should create a unique, easy-to use product that does do what it does greatly. During this course you will learn how to do user research to find out about the goals and problems of your users. Try to find out what really matters for all of them. If you see that you have two different groups of people, find out if they are similar enough to serve them one product. If they differ too much, say goodbye to one of them and design just for one of the groups - maybe you come back later to the other, but first concentrate on one thing.

But what about the products that are used by everyone? In case you want to design something like this you should not apply the suggestions above, right? Well, when I think about products for everybody I think of facebook for example. It has a vast number of users so this is enough "everybody" for a beginning interaction designer I think. Though strangely, Facebook started with a very restricted target group: Students of the Harvard University. Slowly and controlled it was opened to more people. First Students of other elite US universities ("Ivy League"). Than all other US universities. Than Highschool students, employees of several big companys and finally it was open for everybody. I don't want to put them on a pedestal for great interaction design. I just want to illustrate that they are successful and did not "desgin for everybody".

What this illustrates as well is that it is always easier to add features. Removing them if you note that they don't help you is very hard. You can do so but nobody likes it. What if a function that you particularly use would disappears after an upgrade of your favourite software? People suffer incredibly if you take something away, even if the most of them would be better of it what they had would have never existing anyway. Strange, but that's the way it is.

If you release a successful 1.0 Product you can still extend it in the 2.0 version even with features that are not very-super-crucial. But I write this to help you to release a successful 1.0 version so I did put emphasis on the simplicity.