Photography as a medium has captured people's realities since the early 19th century. Over the years, we have employed various imaging procedures without really considering their harmful chemicals. The newest and perhaps the last step we took in this regard was transitioning to sterile digital photography. Unlike film, where light interacts with chemicals, in digital photography, light hits a digital sensor that captures the number of photons hitting each cell in its array of cells. This information can then be digitally processed to resemble the object that was photographed. With the image in the digital realm, it can join the thousands of others on the Cloud. Photography has evolved from capturing important moments like weddings, holidays, and birthdays to being integrated into our cellphones for taking selfies, enabling video calls across the planet, and to maybe spy on us. All of this happens without the need for a chemical process to develop film or print a photo. It seems too good to be true. The use of digital eyes is an integral part of the digital machine that has all of us linked up.

Can you see what the two images have in common? Okay, it's a bit small, but in the right image, my aunt, the tallest one of the three, is wearing the same camera around her neck that I'm holding in the left image. The right image was taken around 1981, and today, around 42 years later, I can still load up a roll of film into that camera and start shooting without any issues.

This is another camera I want to introduce to you. It is now nearly 100 years old, produced in 1926, and is in almost working condition. A bit of lubricating oil has dried up, but that's easy to fix.

Will we be able to use our current technology in a hundred years? When was the last time you switched your smartphone? Does the old one still work, and will it ever be used again?

The most likely case is that it will end up in a landfill somewhere. The digital camera that took photos of my childhood is long broken. The data is still there, but will my grandchildren be able to find it in the attic somewhere? I hope so.

The chemical procedures of photo development were and still are pretty harmful (we also developed new, less harmful chemicals). But the tools we used are still functional today. The impact of the production of today's technology is far beyond that. Technological progression has created incentives to make devices that only last a few years. And it is pretty logical. Do you want the new features that are promised by the new generation or not?

The issue is created by the fast progression of technology, which in itself is something good. New knowledge is the key to a better world — how to feed ourselves, how to protect and understand nature, how to survive tomorrow. In the past, every craftsman had their tools, their own tools. A smith's hammer had grooves in the shape of the smith's hand on the handle — signs of wear that enhanced the functionality of the tool. And that made it a solution that only works for that one specific smith. Today's technology isn't like that. It's designed to be scalable and to work for everyone. This has the big advantage that companies get the budget to push technology further than any single person could. But with that, we rush through so many iterations of a technology that only enhances our individual lives by a little bit.

A solution I could see for that is a culture of everyone becoming their own toolmaker. Companys could take step back from the one solution for all to more openly designed systems that are modular, repairable, and customizable. If you invest time in developing your own tools that you understand and that make a big difference in your productivity, you will very likely keep that tool for far longer and adjust it over time to adapt it to new technologies, maybe by just changing one component.

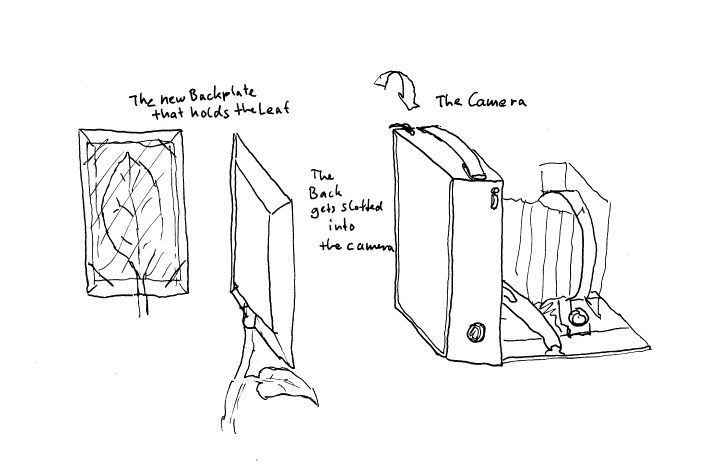

A small step I want to take in this direction is to take this 100-year-old film camera from above and change one component to bring back its functionality and adapt it into the largest modular system called nature. Film cameras use film, and there are different formats of film — small rolls in a casing, bigger rolls, and there also used to be single sheets of film. This camera used these sheets, so if I wanted to use this camera again, I could try to cut up the bigger rolls into fitting pieces, but I could also try something else.

The Camera with two of the backs that can be slid in.

A leaf has adapted to fulfill many roles in the system that is a plant. It creates energy, can store a bit of energy, provides shade from the sun, and can maybe detach and carry a seed. But it is also part of the bigger system of nature. It serves as a building material for insects, composts into nutrients for other plants, or is eaten directly by an animal. All of that and so much more is the role of a leaf.

The chloroplasts inside the leaf take CO2, water, and light to produce sugar. If an excess of sugar is produced, it converts a bit into starch for storage. If we now, by external means, control where this excess is produced, we can use an iodine solution to make the starch visible to us and turn the leaf into a picture. This is the principle behind photosynthesis photography.

Let's adapt the camera so that it takes leaves instead of a film sheet and gives the leaf one more role it can be used for.

(Not finished yet)

References

Is Analogue or Digital Photography More Environmentally Friendly?, https://magazine.urth.co/articles/analogue-versus-digital-photography-eco-friendly

Photosynthesis photography: Making images with living plant leaves, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-qETedzsFIE

Chlorophyll prints – nature expresses itself, https://www.alternativephotography.com/chlorophyll-prints/

Other references

Aby Warburg -- mood boards

Bruno Larour -- ANT Theory

Vannevar Bush -- Memex system